Urban Exploration

The exploration of man-made structures, usually abandoned ruins or hidden components of the man-made environment.

Let me begin by saying that I wouldn’t describe myself as an urban explorer necessarily. Let’s just say I have a penchant for some light trespassing every now and then. And a particular fondness for abandoned buildings. I’m not quite sure where this came from, but there are two things that really interest me. The first is the fascination with something being forgotten about and slowly decaying. Usually something grand or beautiful, but not always. The second is a little more simplistic: the thrill of being somewhere you’re not supposed to.

My earliest memory of this fascination was when I was around 14 years old. There were two old, crumbling houses at the bottom of my parents’ street and I (somewhat stupidly) convinced a (probably equally stupid) friend to explore with me. The date and time were set. Truth be told we had more of a thrill outside the houses, goading ourselves to take the first step and spooking each other by saying that we’d seen somebody inside.

When we eventually stepped into the house we found… an old crumbling house. There was graffiti and general decay in abundance but, alas, no creaking rocking horse in the nursery and no fluttering curtains. Not even a slamming door as evidence of the long-dormant spirits of those who had been there before us. Nope, it was just a house that somebody had left to the forces of disrepair. And one that’s since been knocked down. But even without the jump scares, those irresistible questions that define the thrill and mystery of urban exploration had taken root. What’s the story of this place? Who did it belong to? Who lived here? And why did they leave?

A few years later, I had another go. This time a little further afield. The Bosnian capital of Sarajevo was the place; a city that, for all its beauty, was strewn with bullet holes and the shells of buildings bombed during the Kosovo war. We were walking the city when we stumbled on one of those empty husks. It was easily accessible and instantly tempting. I stared up at the imposing, brutal concrete structure and those familiar questions popped back like cartoon thought bubbles. I wondered who had worked there, what the building had been used for and what events it had witnessed. I told myself that I would just look around the first floor and then leave. Hours later, I was still there. One floor turned into two, which turned into four, and so on.

Unlike the ordinary domestic decay of the houses I’d snuck into a few years before, this was a strangely moving experience. The building had been attacked during the war and lain abandoned ever since. Many desks were still pretty much intact; papers stacked high, the top sheets occasionally ruffled by the wind whistling through the windowless spaces from who knows where. Here and there were items of clothing long left behind and forgotten. How sad that people had to up and leave and never return. Violating perhaps the most fundamental rule of urban exploration – take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints – I pocketed a sheet of paper. When I got home I translated it (Google Translate, obviously – my Bosnian wasn’t quite up to scratch) and discovered the building had previously been a bank. There was an inked signature on the page. I wonder what happened to them.

By the time I found myself in Berlin a few years later, I’d discovered an entire online community dedicated to urban exploration. I’d spent far too much time looking through photos of other people’s adventures. Some local, some bigger, some infamous and dangerous (see: Chernobyl), some unknown and misremembered. But looking at online pics and forums doesn’t make you an ‘urban explorer’, and I wasn’t kidding myself that I was. My holidays weren’t ‘explorations’. But I’d keep my eyes and ears open all the same. If an opportunity should present itself, or I heard about something interesting in the area, I hoped that I could be just bold (or stupid) enough to hop a fence or chivvy myself through a window.

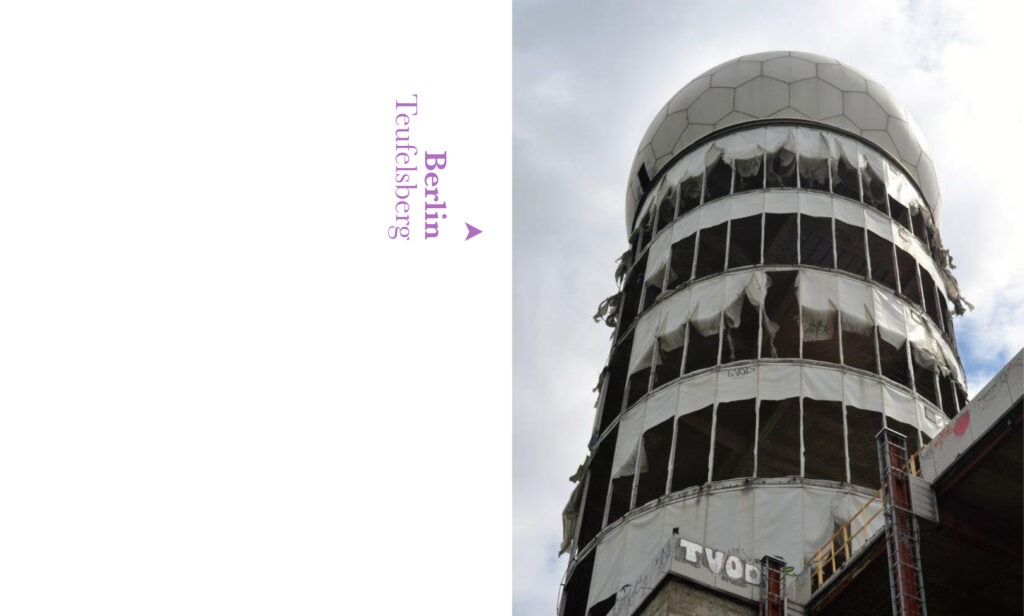

As it turned out, Teufelsberg was a pain in the arse to get to, but easy enough to get in to. A decommissioned Cold War listening station on the crown of a man-made hill, it looms over forest and city alike. Its bulbous radomes sit high above the trees, and as you get closer to the site, you can hear the torn tarpaulin flapping in the wind. Sneaking in through a fence was easy; the site has long been a magnet for street artists, so much so that a portion of the site has since been converted into a tourist attraction where visitors pay an entrance fee to gawp. So it barely counted as ‘sneaking’ at all.

Knackered warehouses and burnouts clustered at the bottom of the towers, while the wall-to-wall graffiti offered a testament to the ingenuity of those with a can of paint and nowhere else to be. The effect is to turn what should be a pretty depressing sight into somewhere that’s awash with colour. A disconcerting but thrilling clash of culture and history. If you venture into the buildings at the bottom of the towers you’re faced with up to five flights of pitch-black stairs to reach the top. But if you can avoid a crunching death, you’re greeted with panoramic views of the Grünewald forest and the skyline of Berlin in the distance. I saw one or two other people while I was there and we never spoke. The unwritten rule of urban exploration is to never engage in conversation and keep your distance. Or at least I think that’s the rule? But sagging sofas on the top of the tallest tower made it clear that people came here to meet and hang out. Turns out that not all derelict buildings are derelict. There was a community here.

Knackered warehouses and burnouts clustered at the bottom of the towers, while the wall-to-wall graffiti offered a testament to the ingenuity of those with a can of paint and nowhere else to be. The effect is to turn what should be a pretty depressing sight into somewhere that’s awash with colour. A disconcerting but thrilling clash of culture and history. If you venture into the buildings at the bottom of the towers you’re faced with up to five flights of pitch-black stairs to reach the top. But if you can avoid a crunching death, you’re greeted with panoramic views of the Grünewald forest and the skyline of Berlin in the distance. I saw one or two other people while I was there and we never spoke. The unwritten rule of urban exploration is to never engage in conversation and keep your distance. Or at least I think that’s the rule? But sagging sofas on the top of the tallest tower made it clear that people came here to meet and hang out. Turns out that not all derelict buildings are derelict. There was a community here.

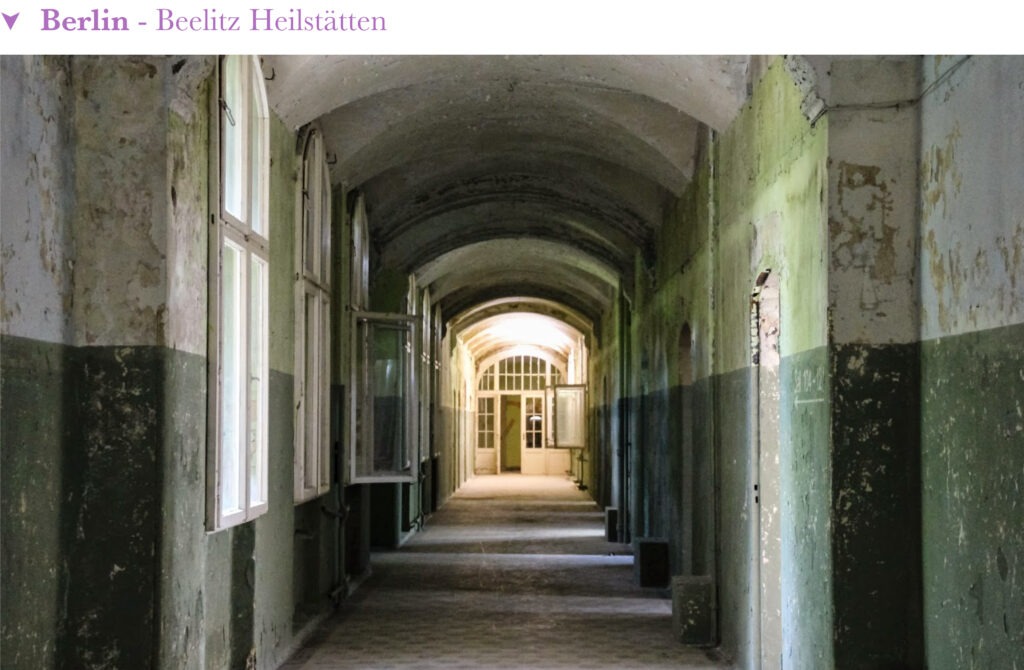

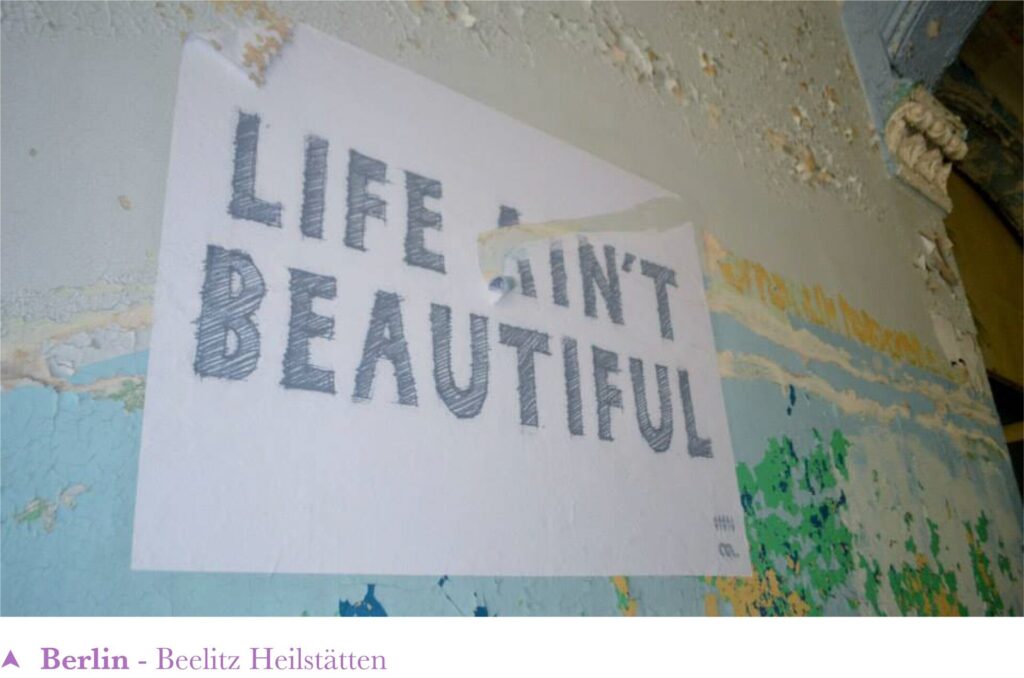

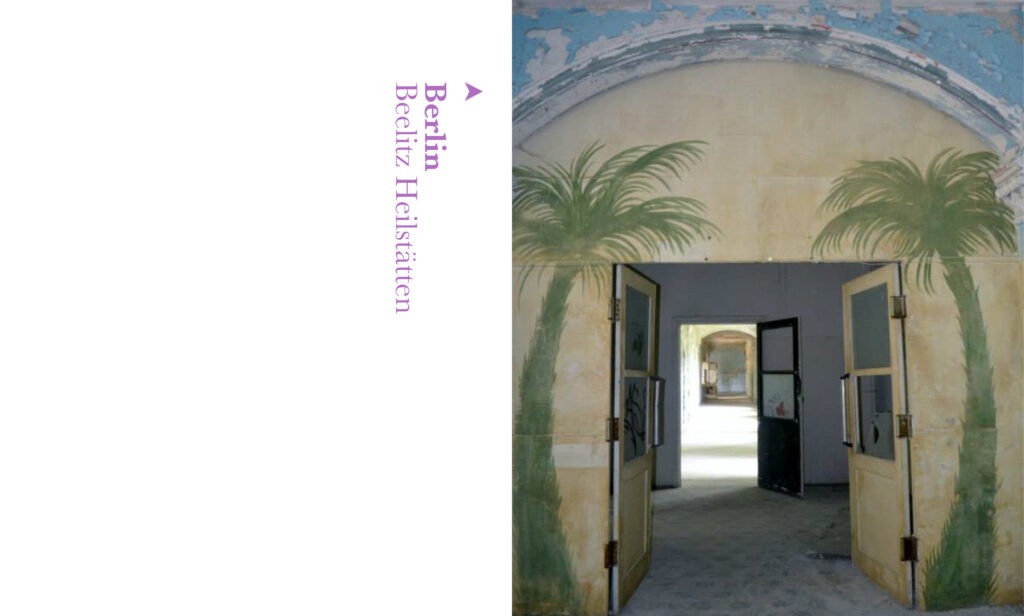

On a more recent trip to the city, I coerced my friend into another trip out of town – this time to Beelitz Heilstätten, an old military hospital south of the city. Reading recent reports it sounds like this site is in the process of becoming a bona fide tourist attraction, so we got there in the nick of time. We found the site totally deserted. We didn’t see another soul. The silence had an air of menace, and more than any other place I’ve been to before or since, it spooked me.

The complex was huge. There were more than 60 buildings in total. Some of them had been lovingly restored, but others lay untouched. Our target was in the latter category, our entry point an old window that we could just about access via strategic deployment of a plank of wood and a serious run up. The buildings were like nowhere I’d ever explored before. Amazingly well preserved and with glass in most of the windows. Rare for somewhere like this, it added to a sense of grandeur undimmed by time. Big, sweeping staircases and ivy-covered terraces gave the space a palatial feeling at odds with its history as a hospital and the rooms were light, bright and airy. As we meandered through the corridors we weaved in and out of the rooms. Entering one, we became aware of a change in the taste and smell of the air, of disinfectant cut with something metallic and raw. The detritus in the room told us that this was an old operating theatre. I’d known already that Hitler and Honecker were both treated for injuries here during the First World War. I allowed myself a macabre vision of them standing in the very room I was in. Or lying, perhaps. We explored a little further but it wasn’t long until the general eeriness had us both wanting out. As we emerged into the sunlight, I turned to look at the building behind us. In the cold light of day I felt a powerful sense of gratitude and awe that I’d had a chance to see it like that.

My most recent expedition was a little closer to home. I’d heard about a place in Leeds: the roof of a tower block. One day after work, having rounded up a willing friend, we set off to explore. The building was a functioning high rise, but we still needed a few smarts to get ourselves where we needed to go. Having climbed a lot of stairs, it wasn’t long until we were staring at the latch of the roof door. We opened, climbed through and shut it behind us.

Even after a good few goes at exploring this sort of thing, reaching the destination still fills me with equal parts excitement and dread. Beneath the adrenaline and drumming heart are those ever-familiar anxieties. What if the latch won’t open again? What if we’re stuck? What if I’m going to end my days on a rooftop in Leeds? What will my mum say when they eventually find my body, skinny and sunburnt and covered in bird poo?! But those worries faded, as they always do.

I stood up and saw my hometown like I’d never seen it before. The sun melting into the dusk, the city lights starting to twinkle, the views stretching to distant horizons on all sides. I walked to the edge of the roof and sat down, my legs dangling over the edge and my blood pumping in my ears*. It was a panorama that seemed to demand some sort of existential contemplation. Was this what I did now? Is this my hobby? It doesn’t seem like the right word, or even the right question. But if you were to ask me whether I’ll pass up the chance to explore the unexplored, see the unseen, or witness a vision of history in its rawest, most unvarnished state? Well, I know my answer.

*For the benefit of queasy readers (and my Mum) I should point out that there wasn’t a sheer drop beneath me and that the immediate risk was more attracting the wrath of security guards than plummeting to my death.